Paper from a lecture

I gave at the ZMO

(Zentrum Moderner Orient)

Berlin, July 18th 2016

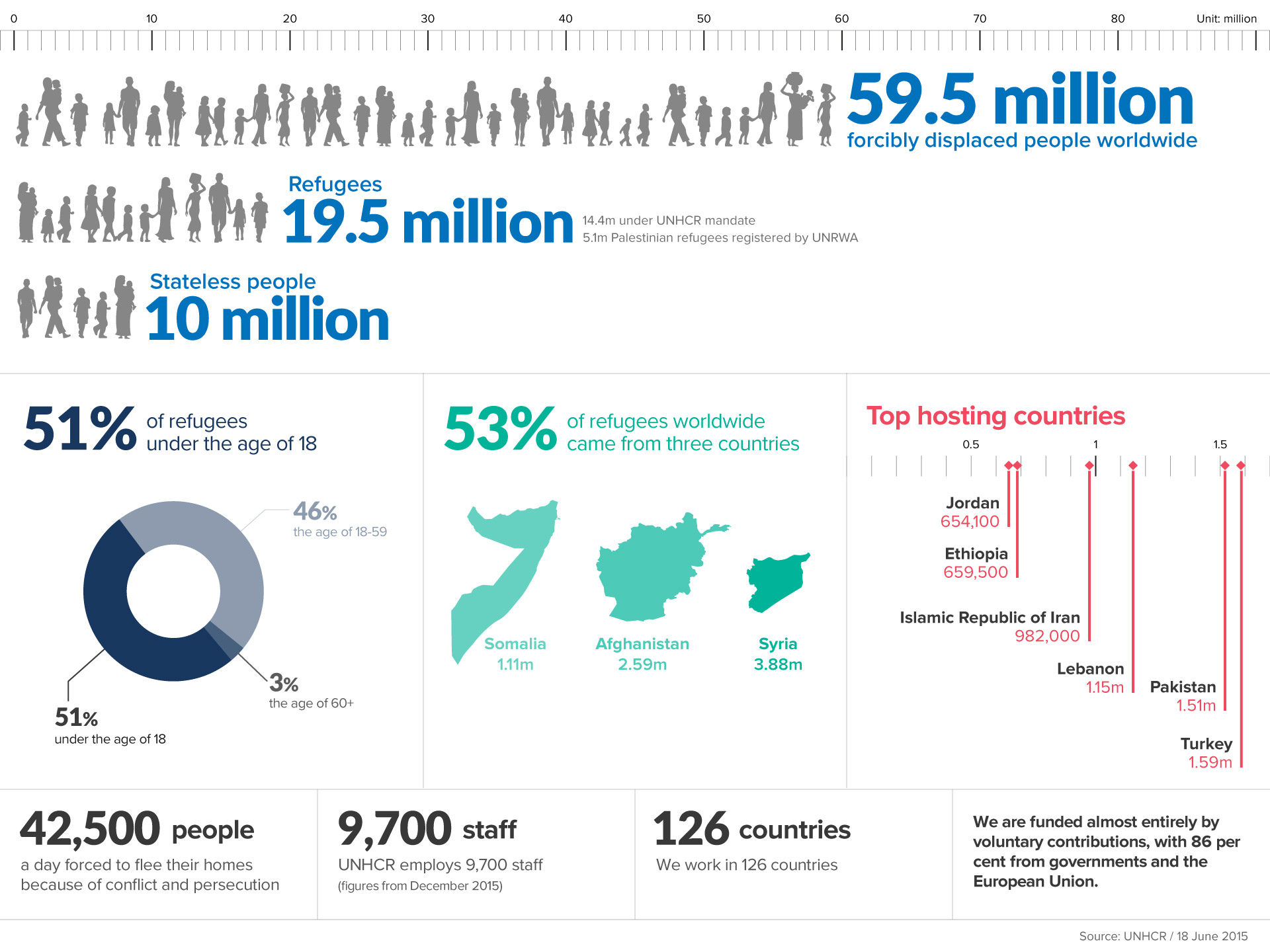

The 2016 ZMO Seminars “Refugees and the city” raised a particular interest because refugees are usually associated to camps, which are, in turn, associated to very negative meanings of the word, such as prisoner camps or concentration camps. With the dramatic increase in the number of refugees[1], the past decades have seen a multiplication of refugee camps in different regions, mainly in Africa, Asia and the Middle East, and recent studies have tried to bring more light to the general public on the situation faced by those populations (see Figure 1 below).

Hardships, promiscuity, confinement, lack of perspective, lack of humanity, sometimes violence, describe the daily life in many of those camps. By the sheer size of some of them, there is also a strong aspect of urbanisation, which should be more carefully studied in order to find new solutions to improve the situation, keeping in mind the diversity and fragility of each case.

The original idea of the refugee camps is to offer those persons, who often fled violence, a secure place, a safe haven as by the mandate of the UNHCR[2]. It is our job, as humanitarian workers to try our best[3] to make sure this original purpose is not lost. Working together with specialists of urbanisation should be part of that objective[4]. Each humanitarian organization has it’s own history and practices, but there is a general consensus on basic principles as for example described in the Figure 2 (Core Humanitarian Standards, CHS)[5]

The present paper only intends to share some experiences of different contexts I came across in the past 10 years of humanitarian work in different areas of Africa, Asia and the Middle East. I have learnt a lot, but foremost the specificity of each case which makes it hard to put it all in one box. Though humanitarian work globally enjoys a positive image, it is ranked by some, including leading scholars, as biased, manipulated, if not altogether neo-colonial. Acknowledging this accusing finger pointed at the work of NGOs and IGOs[6], I would rather see it as questionable but not so doomed. My modest point of view “from the field experience”, could be of interest as it seems less often presented in Universities[7].

A- Refugees, camps, diversity

The situation of the Refugees and Displaced Persons in camps vary widely, depending on a many of factors, such as the level of violence in the area, the political powers at play, the level of funding, and the acceptance from the local population. The size of the camp is also an important factor. Camps hosting over half a million or even a million persons are logistical challenges for which the solutions are seldom humane and person specific. It is more machines of mass management, where urbanisation expertise should be more involved. Moreover, in some areas like the Rohynga camps in Burma, experts see the tension as pre-genocide situations, making the gathering of those groups in the camps an easy target for violence.

As I worked in Chad, on the border with Sudan, I lived in a remote region, in a village between two refugee camps (Brejing and Tregin), which gathered a total of around 50.000 persons. The word « camp » was used to refer to the limited areas where the refugees who had fled violence in Sudan could settle down, and which had been negotiated with authorities (official and traditional) of Chad. The organisation of the basic services was financed and managed by the UNHCR as part of it’s mandate together with Non Governmental Organizations (NGOs). The persons living in the camps were not allowed to settle down somewhere else; therefore could certainly not be considered as a democratic and open system. However, over time and through negotiations with the local authorities if became possible for the refugees to have access to some areas for agriculture, and to built traditional huts. The camps looked a lot like small towns, with services provided by humanitarian organizations instead of private companies like in Europe. People could freely enter and leave the camp; which did not have any kind of fence around it. Inside that area, some people opened shops and started small businesses. It was actually part of the UNCHR funded projects to encourage such commercial activities by providing trainings and small working kits, as well as micro-credit. In the middle of the camp there was a medical clinic, and buildings where school was given daily. It is true that the persons living there could also have been given the possibility to go anywhere else in Chad, or in other countries, but considering the limited financial capacity of the UN and political considerations in the region, it was a governmental decision to offer this type of refuge. It was also hoped that the situation in Sudan could improve allowing the refugees to go back easily over the border. It was always a discussion over the NGO projects to be careful not to go too far in the assistance provided to the refugees, as the citizens of Chad living in the same area, did not have access to the same level of public services / assistance, which could raise tensions against the refugees. Both in the camps and in the village, I was able to walk around, meet and talk to people. Meetings with representatives of the camps and of the village were essential and held regularly to discuss needs and prospective activities. Humanitarian organisations have as principle never to be armed, and though they can use big 4×4 cars because of the local roads conditions, getting off the car and being with the refugees was not a problem.

In this case the « camp » system is in fact a town (see Photo 1 below), of which the residents have limited rights because they are not citizens of the host country, but they have rights as refugees and they benefit basic services. It makes it bearable in the short term, but the camp system is not set up for the long term, unless it is fully turned into a city as it sometimes happens, though the host country often will deny the reality of this evolution and keep the refugees in their refugee status, as non-citizens[8].

B/ Funding limitations and prioritization

A constant question faced by NGOs when trying to bring assistance to populations in need, in particular for displaced populations, is the quest for funds.

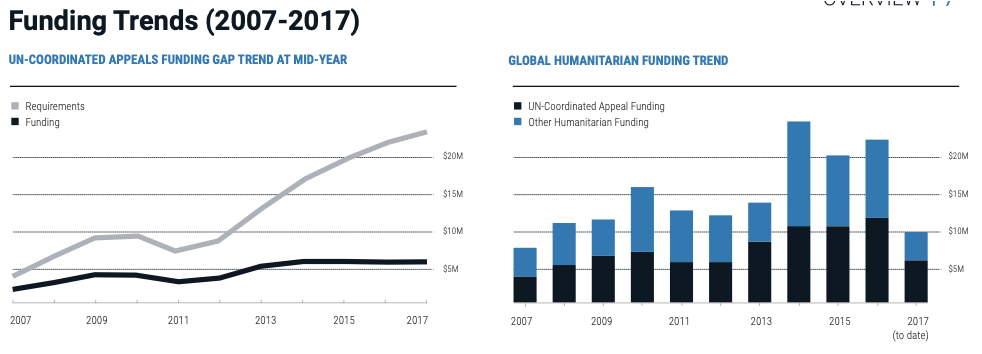

As shown in the tables of the Humanitarian funding trends as of mid 2017, UNOCHA[9], (Figure 3 below), the estimated amounts required by the humanitarian community to cover decent humanitarian actions in all areas where it is need are always much higher than what is in the end attributed to the various institutions. The NGOs have also other sources of funding, but which cannot compensate for this gap.

This gap means that choices have to be made, usually at the intergovernmental level, as to how the limited funds should be attributed. In addition, the level of interest/concern of the international community, and corresponding availability of funds clearly determines the level of services that each case of displaced populations can enjoy.

NGOs enjoying a high level of private funding can sometimes compensate also those political choices by intervening in “underserved” areas, but those funds are limited, and also sometimes attributed by the private donors to specific interventions, limiting the flexibility of its use.

The pictures below can illustrate how basic the “assistance” is when funds are very limited, as was the case for the displaced populations in North Kivu (Democratic Republic of Congo) in 2010.

In the photos examples (see Photos 2 to 6, below), the “camps” in North Kivu had been set up independently by the displaced groups, and the assistance was only minimal, with NFO (“Non Food Items”, such as tarpaulins and jerry cans), and in certain locations, basic WATSAN facilities (Water and sanitation).

C/ Access

In the above example in Eastern Chad, the government agreed that the organisations, local and international, could reach the region to provide assistance. The region is isolated and far from the main cities, but work could be organized and the risks posed by armed groups considered reasonable. This is what NGOs call “access”, which is often a main barrier to bring support to the populations most in need. Very poor road conditions, or harsh climate in winter have to be considered to be able to reach displaced populations, but the main obstacle to access is usually the high level of violence, from isolated small armed groups to full fledged war with daily fights and bombardments (for examples of those difficulties see below Photos 7, and 8).

NGOs discuss at length with all actors at different levels to be able to negotiate access, and only when it is granted, proceed to the evaluation of needs and project implementation. As a principle NGOs do not resort to weapons or armed guards, therefore, this negotiation of access is essential for the safety of the staff and of the populations. Obviously, in volatile areas, this access has to be constantly re-assed and discussed, and it is not a foolproof guaranty against security incidents[10].

D/ Violence

The question of violence on displaced populations was very acute in 2010 (and still is), in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), on the border with Rwanda[11]. There, Internally Displaced Populations (IDPs)[12] gathered in what we called camps, where minimal assistance was provided by international organizations and local employees. The camps where mostly set up independently by the populations fleeing violence in their areas of origin, but again, the camps were not fenced, and people could actually move around the country freely. They were “displaced populations” of DRC, therefore technically not considered as “refugees”. The openness of the camps made night time violence by armed groups easy. Groups would go through the camps to rape, beat up, and steal on a regular basis. The lack of peaceful perspectives in the region offered few other places to go to. The camps usually remained at the level of a village, or very small town. Again, over time, some basic services were provided (water and sanitation, basic household tools), limited in part by the insufficient funds available. Negotiations with local populations opened access to small plots of land for cultivation, and other types of small revenue projects were conducted. Beyond the geographical complexity of the area, the main problems were simply the lack of funds to provide a better assistance, and the constant violence in the region. This underlines, that even though the international organizations are responsible for the support they provide, for it’s quality (even in terms of efficiency and accountability), if funds are not available and if the local, regional, and international community (meaning the States) can not provide a basic level of security, most of the humanitarian work’s impact is limited from one day to the next. Which brings again an essential question, what should be done to help vulnerable populations, which would be undone by armed groups / war the next day?

I also had the opportunity to work for an NGO in Palestine, where we faced those same questions related to the purpose of our work, its impact, and perspectives, in communities of different sizes, from villages of the West bank to suburbs of Gaza. The question of the relation to the other actors was also always very acute, which brings me to another point that I found interesting during this workshop. I heard several times critical points of view on the role of the NGOs and International Organisations, in the crisis refugees face. Obviously, the situations referred to are so complex and volatile, it would be absurd to think that any given actor’s activities does not impact on the situation. However, pointing the finger essentially on the flaws and idiosyncrasies of the NGOs and IGOs, left sometimes in the dark the main responsibilities of the hardship faced by refugees. If the role of the United Nations agencies and NGOs in situations such as the ones mentioned above can/should be questioned, criticised, re-evaluated, and adjusted, it should always be underlined that the refugee situations themselves were not caused by those structures. The States, armed groups, economic interests, regional and international powers at play are responsible[13].

E/ Evergetism – International power games – Solidarity

It was shown time and again how assistance to the poor can be a political tool, in Greek and Roman antiquity[14], as of today. States use it internally with their own populations, and for other groups, sometimes just as political marketing, or as means of influence and bargaining lever with other countries/groups as seen in other presentations of this Seminar. However, there are also persons and organisations, involved in humanitarian activities, which still have a different approach, trying to stay away from governmental agendas[15], and moving on from the traditional stances of evergetism or charity.

Through my experiences in those regions of tension and conflict, I witnessed violence and corruption, but I also often came across what could be called, for lack of a neutral word, solidarity.

I will not go into it’s history as a concept[16] or it’s religious backgrounds[17], but rather underline that even if the humanitarian work can and should be questioned, it should also be understood that many of the people working in that field do have a different approach of their work than that of persons working, for example, in a cell phone shop. I will not mention the “westerners”, whose involvement may be too charged historically to be discussed in this small note, but rather and foremost at work in the humanitarian sector, the local employees of the organizations[18]. Though for sure, the salary and the attraction of the international sector counts in the involvement of people in this field, but the notion of helping what I often heard referred to as « brothers » was also a factor. To many of my local colleagues, as to the local population, though everything could not be given to the refugees, not every right granted, it was clear that they should be welcomed and supported.

The notions of empathy – solidarity – altruism – philanthropy – compassion are part of the motivation to work in the humanitarian sector, and should probably be research more. The recent history in Europe shows that those notions, though seemingly far from our « modern » urban life are still active and sometimes (not always) thriving. Erasing it from interpretations of situations where refugees are taken care of, even if it’s in a camp, is simplifying things too far. In the negative way, this can also be linked to the development of refugee camps management by the private sector, where solidarity/compassion is not a factor; and more globally to the international trend to assimilate NGOs to « contractors », applying notions of efficiency and impact to the extreme, which can sometimes remind one of cell phone shops. This frame of mind needed in humanitarian work could also be compared to what H. I. Marrou considered a necessary virtue for an historian to comprehend fully his subject of research, which he called « sympathy »[19].

A high level of expertise/specialisation is now required by donors to design projects for humanitarian interventions; in addition, the pace imposed to NGOs by the calendars of financing is very fast. However, this spirit of goodwill/benevolence (bienveillance) from the NGO staff and the involvement of the populations in need have to be maintained/strengthened. It should be present from the stage of evaluation of the needs, through to the closing of a project. The donors nowadays tend to take more into consideration external private consultants expertise, which is also needed, but too often at the cost of historical know-how of individuals and associations from the given region. In certain situations, donors would rather finance a newly implanted NGO because it proposes a lower cost for services, rather than an NGO with decades of experience in the area. This question is also connected to the essential concept in humanitarian sector generally referred to as « acceptance ». It refers to how the NGO and its work is perceived by the population. It takes time and mutual understanding to be strengthened, it facilitates the NGO security management, but also how the projects are effective on the long term.

F/ Efficiency, effectiveness, accountability

From a different perspective, the very interesting concept of “effective altruism”[20] is being developed and gaining influence on how assistance funds are allocated and managed. Obviously, no one would want money to be wasted. NGOs and International Organisations have evolved and their work professionalised, far from basic charity of well-wishers. Modern management, accounting, and audit techniques are applied for more efficiency and accountability.

However, too much focus on the donor’s perspective and analysis, putting aside the field level analysis and expertise of the humanitarian community and, even more so, neglecting what the populations consider as their essential needs and priorities, could be hedging again towards paternalism, if not neo-colonialism. The decision of what and how assistance should be provided should always include all parties, which obviously in the end improves the effectiveness of the assistance if the population discussed and agreed to it. How to spend money is political, and even if it’s private funds, the allocation of funds should keep a democratic approach. Putting the accent too strongly on efficiency also raises the question of neglecting the population/persons the most in need, because the most in need are seldom the most efficient to assist. Obviously, providing assistance in remote areas is always less cost efficient than to do so in easy to access and safe regions. Encouraging donors to decide too specifically where and how their money should be spent, also limits the adaptability of the field actors to volatile situations and risks focusing the assistance on trendy topics and regions, putting aside less “marketable” needs.

Everywhere I have worked I have noticed that, at field level, the diversity of the people and the complexity of the contexts always make things a little bit more complicated than what we would like to think of as a globalised world. When only a few days are given to analyse a situation to present project proposals (the evaluation phase), which is appropriate in cases of natural disaster, but much longer analysis is required for complex situations such has the ones faced by refugees in camps and in cities. The current system of budget attribution of the main donors seldom allows this careful and inclusive evaluation time.

The International Organizations are not independent as they should be, first and foremost because they depend on donor supports and votes at the UN. Ever since the end of the Eastern Block, the reform of the UN institutions has been discussed, but never came to any result other than its’ growing administrative complexity. NGOs can also seldom pretend to be totally independent, but many of them do their best to keep their freedom of speech and independent views, in particular from the States. The States (as donor or as recipient of Aid) always had a tendency to consider humanitarian assistance as a tool for non-humanitarian agendas (political, strategic, economic…), and NGOs in particular need to keep their role to make sure that humanitarian principles[21] are respected. The trend to resort to private contractors to do humanitarian work also reinforces the risk of manipulation, under the excuse of adopting extreme business like efficiency.

G/ For the refugees and displaced persons, questions always remain

From my experiences and what I have read/heard so far, it does not seem that definitive good solutions to the problems faced by displaced persons and groups have been found. However, if we identify the hurdles we might be better prepared to overcome them. I could see in particular the following contradictions that I would keep in mind when working with refugees.

-What are historically the main factors allowing refugees to cope best with their situation? What does it tell us for each new situation?

-When is a refugee no longer a refugee, but a citizen, or on the contrary, an inmate? At what stage does the refugee status become a trap?

– Camps for refugees, from State of exception to cities in the making?

-Where is the balance between organized efficient care and de-humanized assistance?

-When does humanitarian assistance encourage communities to leave their homes? Is it always a negative pull factor?

-Do States more and more expect humanitarian assistance to take charge of their responsibilities?

FOOT NOTES:

[1] The 1951 Convention on Refugees and it‘s 1967 protocol give a definition and frame which are the base for the action of the humanitarian actors. A refugee is « A person who owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.“ This Convention develops that, within tight limits, the persons designated as „refugees“ do have rights as per international law.

[2] The United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) mandate is « The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, acting under the authority of the General Assembly, shall assume the function of providing international protection, under the auspices of the United Nations, to refugees who fall within the scope of the present Statute and of seeking per- manent solutions for the problem of refugees by assisting Governments and, subject to the approval of the Governments concerned, private organizations to facilitate the voluntary repatriation of such refugees, or their assimilation within new national communities. » Fall Under this mandate : Refugees, Asylum seekers, Returnees, Stateless persons, Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs). See : http://www.unhcr.org/protection/basic/3b66c39e1/statute-office-united-nations-high-commissioner-refugees.html and http://www.unhcr.org/protection/basic/526a22cb6/mandate-high-commissioner-refugees-office.html.

[3] The support provided is usually based on the « Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Humanitarian Response » (SPHERE Project http://www.sphereproject.org/sphere/en/), and the agencies would base their work on the « Core Humanitarian Standards on quality and accountability (CHS) » (https://corehumanitarianstandard.org/the-standard).

[4] As witnessing/advocacy is part of most organisations’ mandate, NGOs have developped web sites, and publish regular reports on their activities and on specific topics. Some of them also publish periodicals where external expertise is also invited. The NGO Oxfam is particularly famous for the quality of it’s reports (https://www.oxfam.org/en), in France a smaller scale NGO such as Medecins du Monde also publishes the very interestingRevue Humanitaire : enjeux pratiques débats, https://humanitaire.revues.org, or the Journal of International Humanitarian Action (www.jhumanitarianaction.springeropen.com). In Berlin, the yearly « Humanitarian Congress » is also an interesting meeting point (www.humanitarian-congress-berlin.org).

[5]https://corehumanitarianstandard.org/files/files/Core%20Humanitarian%20Standard%20-%20English.pdf

[6] NGOs (Non-Governmental Organisations) refers to organisations, both national and international, which are constituted separately from the government of the country in which they are founded.

IGOs (Inter-Governmental Organisations) refers to organisations constituted by two or more governments. It includes all United Nations Agencies and regional organisations.

[7] This would obviously not concern the many specialised modules of humanitarian response which have been developped in private schools as well as Universities over the past 20 years all over the world.

[8] With this in mind, and considering the wide variety of situations, we should be carefull to globally assosciate refugees living in camps with, for example, Giorgio Agamben’s notion of Homo Saccer as is sometimes done. An assimilation of refugees to persons without rights could be reductive, lacking specificity in our analysis and suitability in the solutions found in the long term. There are however cases where states or armed groups deny to abide by international laws, putting the persons in a lawlessness loophole (see the recent examples in Myanmar or Lybia). Couldn’t the concept of „State of exception“ that Agamben also researched, better relate on a global level to the situation inside and around the refugee camps?

[9] http://www.unocha.org/sites/unocha/files/dms/GHO-JuneStatusReport2017-EN.pdf

[10]On humanitarian workers and security see for example, Aid worker security report 2017 at https://aidworkersecurity.org/sites/default/files/AWSR2017.pdf, which notes that « when measured by body count alone, states are responsible for the highest number of aid worker fatalities. In 2015 and 2016, 54 aid workers were killed by state actors. This was mainly the result of airstrikes by Russia and the US in Syria and Afghanistan and an upsurge in state-sponsored violence in South Sudan.

And on Security management see for example the Study organized by OCHA in 2011, To stay and deliver, good practice for humanitarians in complex security environments, at https://docs.unocha.org/sites/dms/Documents/Stay_and_Deliver.pdf

[11] An example of report on the situation in North Kivu from July 2013 see http://www.unhcr.org/news/briefing/2013/7/51f79a649/sexual-violence-rise-drcs-north-kivu.html

[12] In 2010, the UNCHR estimated at « 2.1 million IDPs in eastern DRC where harassment, human rights abuses, rapes and intimidations against civilians are regularly reported by the local population », http://www.unhcr.org/news/briefing/2010/1/4b5ee9ae9/drc-new-displacement-north-kivu.html. By 2017, UNWomen estimated that over a million women had been raped over 20 years, http://africa.unwomen.org/en/where-we-are/eastern-and-southern-africa/democratic-republic-of-congo.

[13] This goes obviously also in cases of natural disasters, concerning which there is a global trend to develop at the international and national levels some Preparedness Response Plans, and work on what is called Disaster Risk Reduction.

[14] Paul Veyne, Le pain et le cirque, Ed. du Seuil, 1976.The author developped the concept of evergetism in ancient Rome and Greece, underlining how the proverbial sociological stakes of money, power and prestige were central in that aspect of political life. The three play a strong role in international politics, and incidentaly, humanitarian assistance fundings and prioritization.

[15] Already in the 1990s, experts were underlining the risks humanitarian aid was facing, considering it’s role in the dynamic of the conflicts, and the tendency to privatise social assistance, as for example by the Director of research at the Fondation Médecins sans frontière in : François Jean, Le triomphe ambigu de l’aide humanitaire, in Revue Tiers Monde, n°151, juillet-sept 1997, pp 641-658. He was concluding p.658 : « Dès lors, le problème n’est pas tant la politique d’aide que la crise politique qu’elle ne peut résoudre et à laquelle elle participe. C’est pourquoi il est essentiel de cesser d’appréhender les crises comme des catastrophes, de mieux comprendre la dynamique des conflits et de renforcer le sens des responsabilités de tous les acteurs impliqués dans les opérations de secours dans les pays en guerre. Sans même parler des responsabilités politiques des pays occidentaux ou de celles des institutions internationales, les organisations humanitaires doivent, plus que jamais, faire preuve de lucidité et de détermination pour éviter que leur action soit détournée de ses objectifs. »

[16] Which should include, for modern times, Simone Weil’s L’enracinement, prélude à une déclaration des devoirs envers l’être humain, Œuvres Complètes t.V Vol.2, NRF, Gallimard, 2013.

[17] See for example for a brief introduction about the early christian period Dignité des pauvres et pratique de l’assistance, J-M. Salamito, in Histoire du Christianisme, Dir. Alain Corbin, pp. 99-104, Ed. Seuil, 2007.

[18] Not to mention the non-western NGOs which flourish on all continents. The world’s argest NGO is often mentioned to be the Bangladesh based BRAC.

[19]« L’historien nous est apparu comme l’homme qui par l’epokhé sait sortir de soi pour avancer à la rencontre d’autrui. On peut donner un nom à cette vertue : elle s’appelle la sympathie », then quotting Saint Augustin « on ne peut connaître personne sinon par l’amitié », and further, « la valeur, j’entends la vérité, du travail historique sera à proportion de la richesse humaine de l’historien » in Henry Irénée Marrou, De la connaissance historique, Ed. du Seuil, 1954, Point Histoire pp. 92-93 and pp. 229-230.

[20] « …the use of high-quality evidence and careful reasoning to work out how to help others as much as possible,…do the most good, …think about which cause to focus on and how to use your money or your time to start making a difference, right away ». See : https://www.effectivealtruism.org, and the work of Peter Singer.

[21] As mentioned above the widly supported principles, as defined for example by the European Commission are : The principles of humanity, neutrality, impartiality and independence are grounded in International Humanitarian Law. All EU Member States have committed to them by ratifying the Geneva Conventions of 1949. Humanity means that human suffering must be addressed wherever it is found, with particular attention to the most vulnerable. Neutrality means that humanitarian aid must not favour any side in an armed conflict or other dispute. Impartiality means that humanitarian aid must be provided solely on the basis of need, without discrimination. Independence means the autonomy of humanitarian objectives from political, economic, military or other objectives.

https://ec.europa.eu/echo/who/humanitarian-aid-and-civil-protection/humanitarian-principles_en

Figures, graphs and photos:

The photos are my own. Copyright © time.solar

Figure 1: Main figures on displaced persons (UNHCR, 2017)

Figure 2: Diagram of the 9 commitments set by the Core Humanitarian Standard on Quality and Accountability (CHS)

Figure 3: Humanitarian funding trends as of mid 2017. Source: UNOCHA

Photo 1: Bredjing refugee camp, Eastern Chad, 2008. A city of it‘s own in a very remote country side (pop. 30.000)

Photos 2 to 6: Displaced populations camps in North Kivu (2010)

Photo 7: For security reasons, people go to the market in large groups, usually protected by a few UN soldiers in armoured vehicle (North Kivu, 2010)

Photo 8: This main road of Daykundi Province in central Afghanistan in winter shows how hard to reach areas, not to mention security issues, can impact the efficiency/cost of the services.

Thank you note:

Many thanks to the ZMO in Berlin for a fruitful and interesting opportunity to exchange on those matters, and many others.

IMAGES

MEMOS

BOOKS

CONTACT

Lastest comments